This post is the first in our two part Champagne Series.

Click to view the second post, Champagne 101: Different Styles and Levels of Sweetness

Whether you’re celebrating one of life’s many milestones, ringing in a new year, or you just want to feel like a rockstar, no other wine says “festive” like Champagne. The following information will serve as a basic introduction to Champagne, and explain why it is unique among the world’s sparkling wines.

The Champagne Region

Champagne comes exclusively from the Champagne region of France, which is located directly north of Burgundy. Like the wines of Burgundy, Pinot Noir and Chardonnay play a crucial role in the production of Champagne, along with the Pinot Meunier grape. Champagne wines may be produced in both white and rosé colors, from one grape variety or as a blend, and from a single harvest or several. Champagne also holds the distinction of being the only appellation in France that is permitted to blend red wine with white in order to make rosé wine.

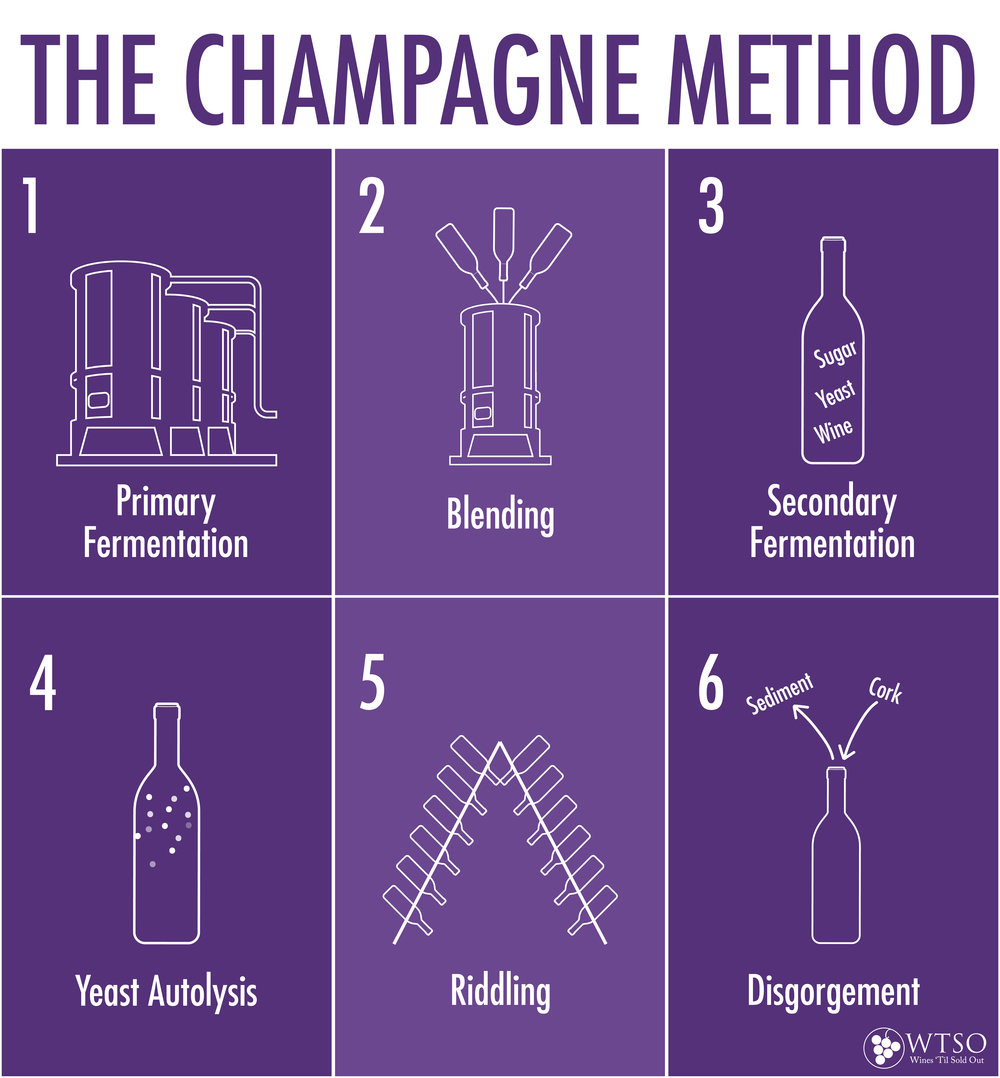

The Champagne Method

Also known as the “Traditional Method,” the “Champagne Method” of sparkling wine production requires the wine to undergo two fermentations, wherein sugar is converted into alcohol.

Primary Fermentation – After harvest, the grapes are carefully pressed, and the juice goes through an initial alcoholic fermentation – usually in stainless steel tanks. The result is known as the “base wine.”

Blending – Next, base wines are blended together. Some of the base wines are saved for later use, and a large selection of base wines ensures that a Champagne producer will have a consistent “House Style” from year to year.

Secondary Fermentation – Now the blended wine is moved into a clean vessel where a mixture of wine, sugar, and yeast is added. The wine is then bottled, and a second fermentation occurs inside the bottle. Bottles are then capped and placed on their sides. This process encourages the formation of carbon dioxide bubbles.

Yeast Autolysis – After fermentation is complete, leftover sediment and lees (dead yeast cells) dissolve into the wine, usually for four to five years. This imparts the bread, biscuit, or pastry aromas and flavors we often associate with sparkling wines from Champagne.

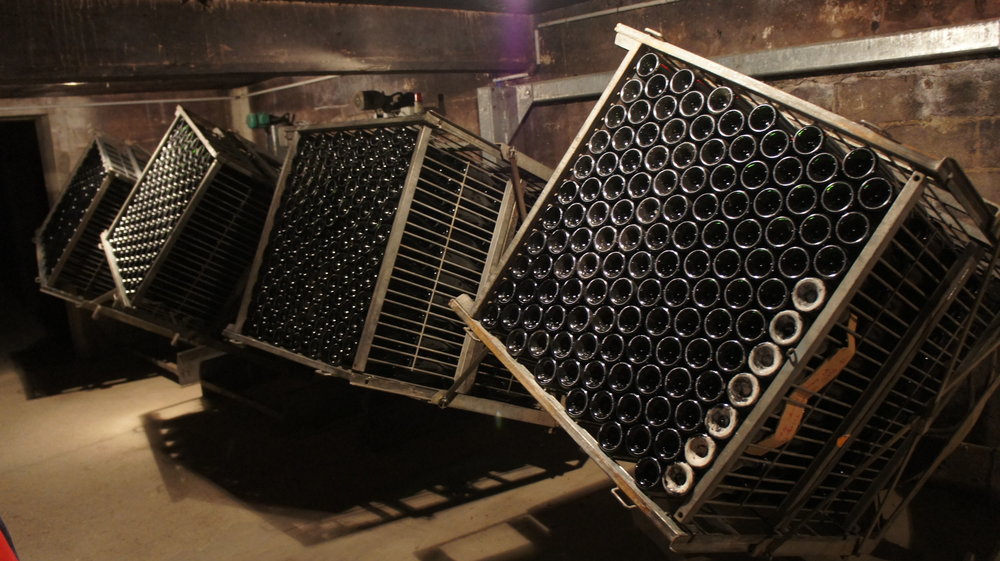

Gyropallette. By G.Garitan CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Gyropallette. By G.Garitan CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Riddling – Once yeast autolysis is complete, all sediment and lees must be removed from the bottles. Traditionally, this was manually accomplished by delicately turning the bottles a few degrees each day over two months until the yeast sediment collected in the necks of the upturned bottles. Today, most producers use a mechanical device, known as a gyropalette, to achieve this step in a much shorter period of time.

Disgorgement – The wine within the necks is then frozen and the bottles are turned upright. The caps of the bottles are removed, and the carbon dioxide inside forces the yeast sediment out. Finally, the dosage, a mixture of wine and cane sugar, is added to the wine before it is sealed by a cork and wire cage. This will determine the level of sweetness in the finished Champagne.

Vintage or Non-Vintage?

Wines from Champagne can come from a single harvest or from a blend of multiple harvests. Vintage Champagne is only made from the harvest of an excellent year and generally commands higher prices than Non-Vintage (NV). Non-Vintage Champagne is always blended from several years to maintain consistency.

Learning about Champagne is important, but nothing can replace the experience of drinking it. There’s never a wrong time to crack open a bottle of bubbly, pour a glass (or two), and toast to life. Cheers!