Oregon is distinct from its neighbors on the West Coast of the United States in terms of climate, history, and wine culture. Whereas California and Washington have warm, sun-drenched weather, Oregon has cool summers and cold, wet winters. California and Washington both have large tracts of land dedicated to large-scale, industrial winemaking, as opposed to the small-scale estate wineries, which promote themselves as simple, sustainable, family farms, dominating in Oregon. The Oregon wine industry is relatively young and small, but is garnering a reputation for distinctiveness and excellence.

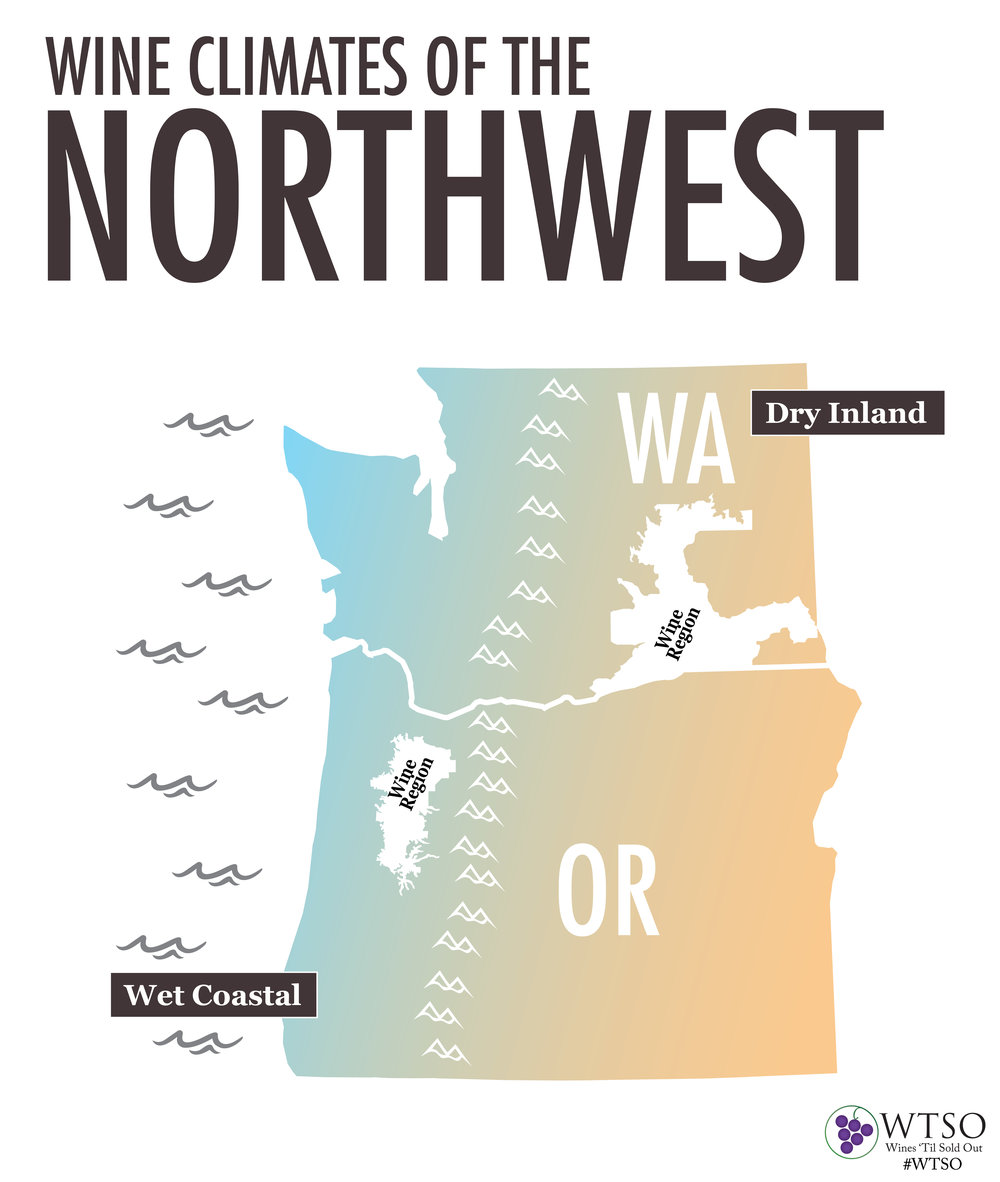

The wineries in Oregon tend to be in the western part of the state, where they are exposed to the moisture and cooling influence of the Pacific Ocean. The majority of Washington’s vineyards, by contrast, are found in the dry, desert conditions further east where influence from the sea is minimal. Grapes in Oregon struggle to ripen, and are constantly under threat from spring and autumn rains, rot, insects, birds, and lack of sunlight. The challenges to winegrowers are so great, that experts claimed traditional, European style-viticulture was impossible in Oregon, as late as the mid-twentieth century. In the 1960s and 1970s, a small number of pioneering winemakers recognized the climate of the Willamette Valley in Oregon for its similarities with Burgundy in France, which is also characterized by cool climate and difficult growing conditions. (Willamette is pronounced “will-AM-it,” not “WILL-am-it” or “will-am-ET”). These innovators planted the red grape of Burgundy – Pinot Noir – in Oregon, and the rest is history.

The first winemaker to plant Pinot Noir in Oregon was Richard Sommer of Hillcrest Winery in 1961. He planted Pinot Noir and various Alsace varieties on an old turkey farm in the Umpqua Valley. A graduate of UC Davis, he ignored his professor’s warnings that his experiments in Oregon were doomed to fail. In 1963, another young winemaker from UC Davis, David Lett of The Eyrie Vineyards, planted the first Pinot Noir in the Willamette Valley. His 1975 vintage Pinot Noir put Oregon on the map, when it placed second in a French wine competition against Pinots from Burgundy. The eminent Burgundian wine merchant Richard Drouhin was so impressed that he purchased an estate close to the Eyrie, and began growing Pinot Noir himself. Since that time, the wine industry in Oregon has boomed, with vineyard area doubling in the ten years from 2003 to 2013 alone.

There are now many subregions in Oregon that have been officially recognized as AVAs, or American Viticultural Areas. Many of these AVAs are located in the Willamette Valley, including Dundee Hills, Eola-Amity Hills, McMinnville, Chehalem Mountains, Ribbon Ridge, and the Yamhill-Carlton District. There are also many areas outside of the Willamette Valley that have excellent wineries, like the Applegate Valley in southern Oregon, which is warm enough to produce varieties like Syrah, Merlot, and Cabernet. Other significant southern AVAs include the Umpqua Valley and Rogue Valley. There are also two warmer AVAs in eastern Oregon: Columbia Valley and the Snake River Valley.

The wines of Oregon offer excitement to enthusiasts who like slightly drier, more restrained styles, and the variety that comes from vintage variation. The trend toward biodynamic and organic farming in Oregon is also appealing to many consumers. The Pinot Noirs from Oregon are among the most food-friendly red wines in the world, and many are showing potential for aging. Pinot Noir is not the only great wine from Oregon. Many cool climate varieties are being grown successfully, including Gamay, Chardonnay, and Pinot Gris. Time will tell what the next phase of evolution will bring to the Oregon viticultural community, but if history is any indication, it will continue to delight wine lovers around the world.