The word “phylloxera” comes up surprisingly often in wine writing. You’ll see references to it in descriptions of vineyards and winery histories, but it is not commonly explained. This article will introduce you to phylloxera, and help you to understand the terminology associated with this horrible little pest.

Before we get into the details, let’s examine two of the most common terms related to the insect.

Example 1: “Ungrafted” – a word used to describe vines that grow naturally on their original root system. These vines are considered by some to produce superior wine, but they are much more delicate and susceptible to phylloxera infestation and death. We’ll discuss this in more detail later.

Example 2: “Pre-phylloxera” – a reference to the period of time before phylloxera became an issue in a given vineyard or region. In most areas, the pre-phylloxera period ended in the mid-nineteenth century.

An American Invader

When the Viking explorer Leif Erikson traveled to the east coast of North America around 1000 AD, he called it “Vinland,” after the large number of grapevines that he found growing in the wild. These vines were highly prized by later settlers, and by the nineteenth century, they were being imported to European gardens. Little did the enthusiastic botanists know that a tiny insect called “phylloxera” had hitched a ride from the untamed forests of the New World to the manicured gardens and vineyards of the Old World.

When the first vines began to die, worried viticulturalists blamed everything from the weather to the wrath of God. By the time they realized that an almost imperceptibly small insect was responsible, they were facing a crisis. From 1875 until 1889, wine production in France alone fell by about three quarters. Aside from a few vineyards situated on sandy soil – therefore inhospitable to phylloxera – it looked as if the world’s wine industry was facing an almost apocalyptic disaster.

Attempts To Fight Back

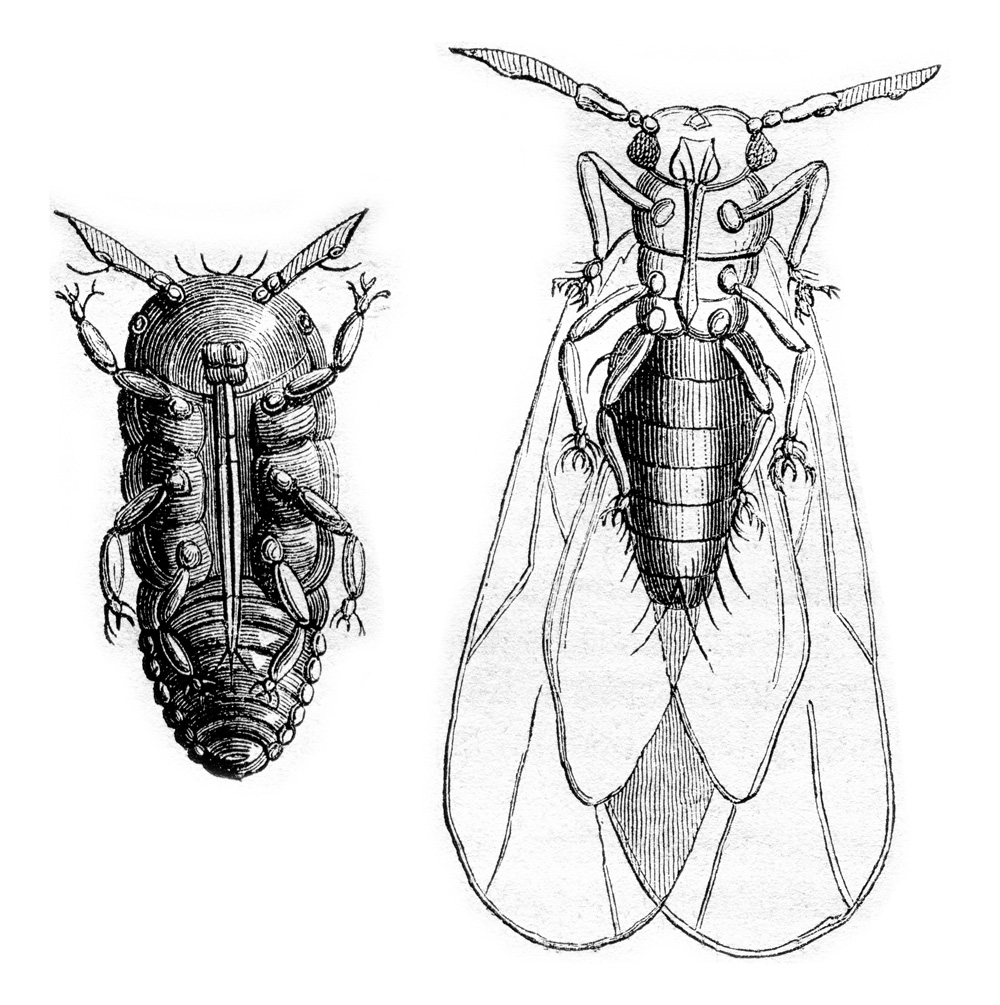

When the first European scientists began to recognize tiny bugs as the cause of their troubles, they named it Phylloxera vastatrix, or “the devastator.” At first, they didn’t know where it came from, but soon it was made clear that it was from America, and had been previously named Phylloxera vitifolli. Proposed solutions ranged from the curious suggestions of irrigating with white wine and burying toads at the base of the vines, to the more understandable ideas of flooding vineyards and utilizing treatments of carbon bisulfide. Of these options, flooding was the most successful, but only worked in vineyards that were on level ground and near a large water supply. In the end, America supplied not only the problem, but also the solution.

Rootstock Saves The Day

The traditional European vine used for wine production (vitis vinifera) is a different species than those found in America. Native American vines had evolved in tandem with Phylloxera, and had developed resistance to the pesky bugs. Vinegrowers had known for millennia that a cutting can be taken from one vine and fused to another, in a process called “grafting.” At the end of the nineteenth century, it became clear that the solution to phylloxera was to plant American vines throughout the world, and graft European vines to the roots. Phylloxera only attacks the roots, so the European vines were safe – as long as they remained above the surface of the ground.

To this day, 85% of vinifera vines are grafted to American rootstock, in order to survive phylloxera – which is still distributed around the world. A few places are safe from phylloxera, including Chile, parts of Australia, and winemaking regions with particularly sandy soils, like the Island of Santorini in Greece. The phylloxera disaster had a major impact on the world of wine. For example, parts of Bordeaux were originally dominated by Malbec and Petit Verdot grapes, which now play only a minor part in blends, since they don’t graft as well as Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot. Fortunately, we have learned to mitigate the damage caused by phylloxera so that we can continue to enjoy wine for generations to come.