Perhaps the most awkward part of formal wine service, the presentation of the cork is often glossed over by both dinner guest and sommelier. What should you do when a server or wine professional lays a cork on the table and looks at you expectantly? I once heard a story of a wine executive making a joke of the whole affair by cutting off a piece off the cork with his steak knife, tasting it, and declaring it “excellent” much to the shock and confusion of the sommelier. This post will give you some ideas of what to look for when evaluating a freshly pulled cork whether at a restaurant or at home.

Keep in mind that visual and aromatic evaluation of the cork only presents you with clues about the wine – the real test is in the glass itself. If a wine smells and tastes good, the cork did its job, regardless of its appearance.

History

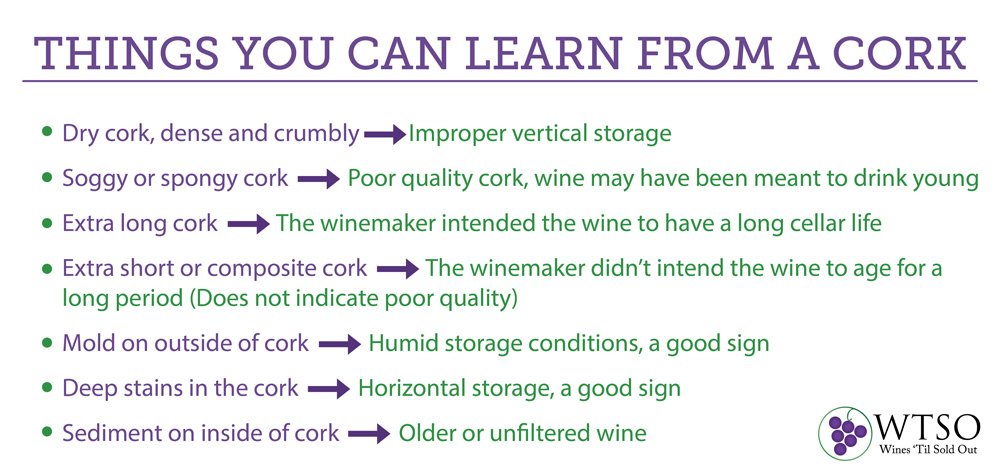

Corks come from the bark of a particular species of oak primarily grown in Portugal, though cork forests also thrive in other Mediterranean areas like southern France, Catalonia, and North Africa. The cork tree produces bark so thick that it can be harmlessly stripped every nine years or so. Cork closures became widespread as the use of glass bottles spread across Europe during the 17th century. Grading takes place on the basis of appearance, with the most uniform textures fetching the highest prices. The most expensive corks consist of a single, smooth piece of cork. Longer corks indicate optimism on the part of the winemaker that the wine will age for a long time, while a shorter cork implies a wine intended for short-term drinking.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the introduction of composite corks made from small pieces molded together into the appropriate shape. These corks have a good track record for short-term use but may not prove ideal for long-term aging. They are the least expensive corks on the market.

Dry Corks

The most basic thing to consider when evaluating a cork is its moisture content. Is the top of the cork dry? Is the bottom of the cork wet? The answers to these questions may help to reveal the storage conditions for the bottle. Storing a bottle in an upright, vertical position can cause the cork to dry out and shrink, allowing air to seep in and cause spoilage. Wine should be stored on its side so the cork stays saturated and allows it to maintain its seal. Therefore, the cork from a properly stored bottle will pick up more and more color over the years, while a cork from a poorly stored bottle will look relatively clean. Sparkling wines are bottled under pressure and last longer than still wines when stored upright.

Storing the bottle in a humid environment also helps to prevent the cork from drying out and spoiling the wine. So, if you find that a cork has mold on the top before opening, it might actually be a good sign. The humid conditions that allow a cork to maintain its seal can encourage mold. Beware of corks that look too dry and clean, especially if they are dense and light – they may indicate vertical storage in a dry environment. As long as the cork isn’t soft and spongy, it’s okay for it to be a little moldy on top and saturated with wine throughout.

Tartrates and Sediment

As wine ages, various substances like tannin and tartaric acid can precipitate out of the liquid to form solids. In bottles of white wine, these solids, called “tartrates,” look almost like salt or tiny crystals and are harmless and natural. Most wineries go to great lengths to remove tartrates from wine because consumers are often afraid of them. The process of removing tartrates, however, also removes some flavor. So if you see them on your cork, don’t worry – they don’t hurt a thing and may indicate a producer more concerned with quality than with public perception.

In red wines, the tartrates are coated in pigment and tannin and look more like dirt than salt. Solids in red wine are referred to rather generically as sediment. Sediment in the bottle or on the cork can indicate multiple things including:

- The wine was particularly tannic when bottled

- An older wine

- An unfiltered wine

- All of the above

None of these factors imply an inherent flaw, so the appearance of some particles on the cork should not be a cause for alarm. If the sediment is especially thick, try decanting.

Looking at the cork can tell you a lot about a wine including its age, how well it was stored, and how it was made – but as the old saying goes, “don’t judge a wine by its cork.” I’ve been surprised more times than I can count by a wine that didn’t match my expectations based on the cork.